For the first time in modern U.S. history, men are just as likely to be religious as women. And the change is being driven by young men.

This represents a substantive shift among the faithful: For decades, women were always more devout, both in Christian churches in the U.S. and around the world. And they were the ones who traditionally have been the lifeblood of congregations, in terms of both attendance and volunteering and organizing.

Why We Wrote This

Why would young men be more likely to attend services than women, when the reverse has been true since at least the 1950s? The answer may lie in a more masculine version of Christianity.

The shift has been ongoing for the past five years or so, to the point that both Generation Z and millennial men and women are now equally religious, says Ryan Burge, a political scientist and former Baptist pastor.

“It’s not like the gender gap has been reversed,” he says. “It’s been eliminated.”

For the first time in modern U.S. history, men are just as likely to be religious as women. And the change is being driven by young men.

This represents a substantive shift among the faithful: For decades, women were always more devout, both in U.S. churches and around the world. And they were the ones who traditionally have been the lifeblood of congregations, in terms of both attendance and volunteering and organizing.

The shift has been ongoing for the past five years or so, to the point that both Generation Z and millennial men and women are now equally religious, says Ryan Burge, a political scientist and former Baptist pastor.

Why We Wrote This

Why would young men be more likely to attend services than women, when the reverse has been true since at least the 1950s? The answer may lie in a more masculine version of Christianity.

“It’s not like the gender gap has been reversed,” he says. “It’s been eliminated.”

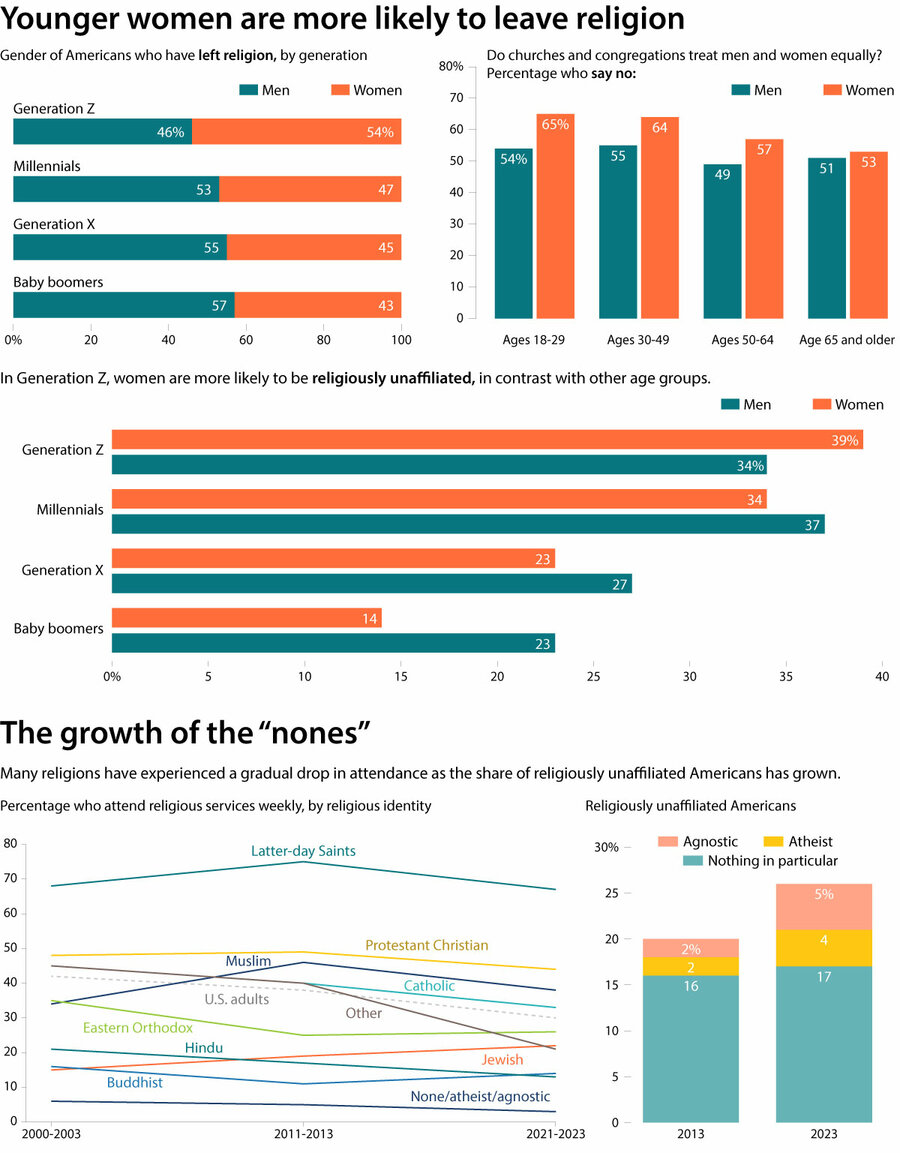

Church attendance across all age groups is down, and the least likely to attend are 18-to-29-year-olds. But the young people who do show up in houses of worship are more likely to be men. Even as Gen Z women continue to leave churches, their male counterparts are joining congregations in higher numbers.

One important caveat: The only religious group in America that’s seeing significant growth is the “nones,” a category including atheists, agnostics, and those who describe themselves as unaffiliated. That increase is also driven mostly by Gen Z and millennials. Older women are still more likely to attend church than older men, but that gender gap shrinks among younger generations.

Zooming in on religious affiliation, the map becomes more complicated. Youngish women are more likely to be evangelical than youngish men, says Mr. Burge. Youngish men are more likely to be Catholic. Mainline Protestants run about even.

In part, the changes now might be the delayed effects of a more masculine Christianity that popped up over a decade ago, driven by leaders like Mark Driscoll, a West Coast pastor known for preaching a dominant, traditional masculinity. While that message brought young men in, “it was a little more repellent to young women,” says Mr. Burge.

“There’s been a culture of masculinity, especially within white evangelicalism,” agrees Katie Gaddini, a sociologist who wrote a book about why single evangelical women leave the church. Among young women who do attend on Sundays, she says she’s interviewed those who say they like President-elect Donald Trump because he reminds them of their father or pastor.

On the other hand, scholars including Alan Cooperman, director of religion research at Pew Research Center, caution that the changes to America’s religious landscape are still too new to be called a trend. The nones category is still made up of more men than women, though that could change over time if women continue to leave organized religion behind.