With the self-assurance of an entrepreneur and the bluff of a big-time poker player, President Donald Trump inaugurated a new and uncertain era in U.S. trade relations this week.

Hours before he was to initiate punishing 25% tariffs on America’s two largest trading partners, Mr. Trump agreed to a one-month delay. No trade missions to hash out details. Instead, the president relied on direct one-to-one calls with the leaders of Mexico and Canada to seal deals.

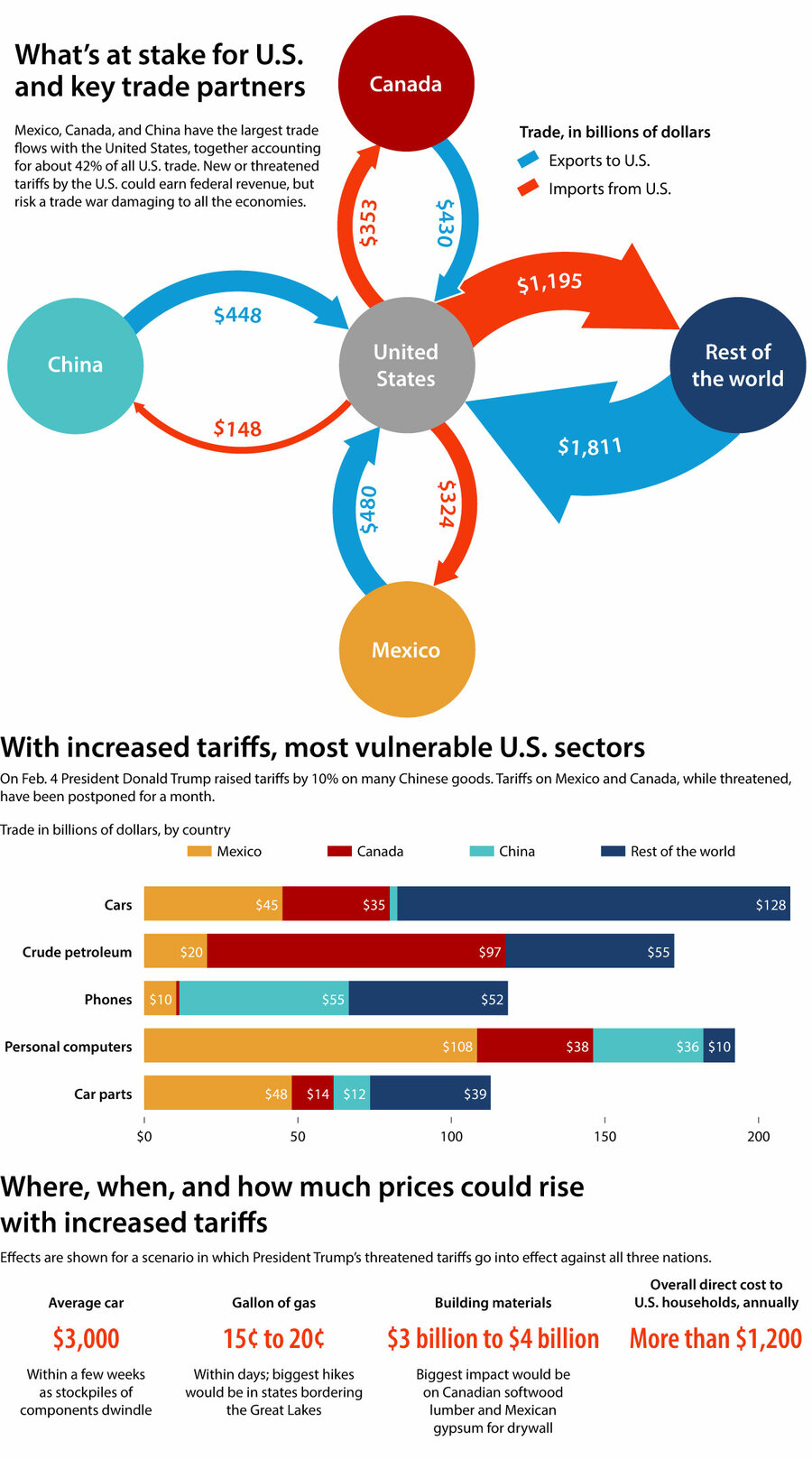

In exchange, they agreed to step up border enforcement initiatives they had already begun. By contrast, America’s third-largest trading partner – China – retaliated with tariffs and other measures of its own when Mr. Trump initiated a smaller 10% rise in the existing duties against it.

Why We Wrote This

In postponing some threatened tariffs but not others, U.S. President Donald Trump is sowing uncertainty for businesses and consumers in his own country and abroad. His tactics could score some wins, but also carry big risks.

It’s not clear he really got that much in concessions from Mexico and Canada. Still, he is expected to use such tactics again.

“Trump will keep using the tariff threats to get little wins, little victories in his dispute with Mexico over the three key themes” of migration, security, and trafficking, says Víctor Gómez Ayala, professor of macroeconomics at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico.

“Obviously, this uncertainty is not going to go away,” says Dan Kelly, president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. “We’re going to have to sleep with one eye open for the next four years.”

At some point, however, the tactic could alienate even close allies like Mexico and Canada. And like China, they may call Mr. Trump’s bluff with tariffs of their own. Immediately after a 10% U.S. tariff went into effect Tuesday on all goods imported from China, Beijing announced that starting Feb. 10 it would impose a 15% tariff on certain types of coal and liquefied natural gas from the United States and a 10% tariff on crude oil, agricultural machinery, cars with large-displacement engines, and pickup trucks.

This tit-for-tat response threatens to reignite the U.S.-China trade war of 2018-2019. A North American trade war would hit the economies of the U.S., Canada, and Mexico even harder. The stakes are high (see chart below).

Tariffs act like a tax on importers. As a result of the new China tariffs, a U.S. company that buys Chinese-made smartphones worth, say, $1,000 will have to pay the federal government 10%, or $100. The firm either absorbs that extra cost or passes it on to consumers in the form of higher-priced phones.

The new tariffs against China would shave U.S. economic growth by only about 0.1% and raise federal revenues (and tax Americans) by about $241 billion, according to the Tax Foundation.

Some analysts believe U.S. consumers won’t notice much of a price hike, but they’ll pay a little more for Chinese electronics, machinery, and games. Eventually, companies can adjust their supply chains to manufacture or buy elsewhere, but the process is generally very slow. Despite seven years of higher tariffs and their short-term trade war, the U.S. still buys hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods each year.

Intertwined economies

If decoupling from China is hard, doing the same with Mexico and Canada would require even more effort. That’s because so many industries have deeply intertwined operations, from lumber and fishing to paper and other manufacturing, says Kristin Vekasi, a political scientist at the University of Maine.

“It would really take … reconfiguring supply chains in a lot of the big core industries that we see, particularly in the Midwest,” she says.

Take automobiles. A car part can move across U.S., Canadian, and Mexican borders six times or more as assemblers add value. In Mexico, lower-wage workers fashion car parts and assemble vehicles destined almost exclusively for the U.S. market.

Yet the across-the-board tariffs President Trump threatens to impose in one month take no account of this back-and-forth integration. By one estimate, charging U.S. automakers 25% each time a part or car crossed into the U.S. would boost the average price of a new “American” car by some $3,000.

In all, the Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates the 10% tariffs on China plus the still-looming 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada would cost U.S. households more than $1,200 a year in price hikes for everything from a newly constructed home to gasoline.

The losses could be even greater in the rest of North America. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce, in a recent estimate, said Mr. Trump’s tariffs would cost Canada’s consumers more than U.S.$1,300 per person annually.

The tariffs would reduce demand for vehicle manufacturing by more than 15% and agriculture by 8%, estimates University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe. The exact impact is hard to predict, he says, because “We have never, ever in modern times gone through this kind of trade policy shock.”

Mexico is especially vulnerable. After the U.S.-China trade war, multinational corporations operating in China diversified by opening new operations in Mexico. They began exporting to the U.S. everything from completed cars and semiconductors to flat-screen televisions and avocados.

But the multinationals that moved into Mexico can also move out if U.S. tariffs persist. And with about 40% of its economy dependent on exports (of which the vast majority go to the U.S.), Mexico has little leverage to negotiate with Mr. Trump. If he imposes 25% tariffs, the nation faces prospects of major industrial downsizing and job losses.

Where will the trade bargaining end up?

The president’s high-stakes negotiating style also injects uncertainty into the political and economic decision-making. On Monday’s call with Mr. Trump, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo agreed to send 10,000 national guard troops to patrol Mexico’s northern border. That’s roughly five guardsmen for every mile of border. In return, she got a one-month delay in the imposition of tariffs and, she said, a pledge to stop the flow of U.S. weapons into Mexico.

It’s her latest visible effort to meet his demands to curb the trafficking of drugs and migration into the U.S. In her four months in office, her administration says it has seized 40 tons of drugs and arrested some 10,000 people connected with drug trafficking organizations.

Also on Monday, Mr. Trump issued a last-minute, one-month delay on Canada tariffs. In a call, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he would implement an already-announced U.S.$900 million border plan, appoint a “fentanyl czar,” officially list drug cartels as terrorist organizations, and create a joint anticartel strike force with the U.S.

This high-drama negotiating is not only keeping nations guessing, but also making it harder for companies to plan investments. Will the tariffs be imposed? How long will they last? Answers to these questions will determine if and when companies move – typically a multiyear process of planning and implementing.

“This is the crazy part,” says Hâle Utar, an economist at Grinnell College in Iowa, about the day-by-day uncertainty. “Investment doesn’t move like that. … Trade wars are expensive, especially with your neighbors.”