As he moves to dismantle the legacy of free-trade capitalism popularized by President Ronald Reagan four decades ago, Donald Trump is entering a perilous phase of his new presidency.

Elected to fix the economy, President Trump appears poised to slow it down. Having promised lower prices, he has imposed tariffs that will raise them. It’s a high-stakes move, perhaps premised on the idea that Americans will forgive the short-term tariff pain if they realize longer-term economic gains from his other reforms.

That outlook has a certain logic. Unlike the classic inflation spiral under former President Joe Biden, Mr. Trump’s tariff-lation is expected to act more like a one-time price hike. It should dissipate as supply chains and currencies adjust. That could give the president time to extend tax cuts that proved highly popular during his first term.

Why We Wrote This

In times of uncertainty, people and businesses often slow their spending. It can cool the economy even beyond the direct effects of higher prices from tariffs.

“It may be a little bit of an adjustment period,” the president acknowledged Tuesday night in his first speech to Congress since his return to power. “Bear with me.”

Several factors could upset this strategy, however, including the one most difficult to forecast.

“Uncertainty,” says Andrew Berger, president and CEO of the Indiana Manufacturers Association, which represents more than 1,100 companies in the state. “It’s just terrible for business.”

Tariffs are inflationary

Already, uncertainty is growing. Such uncertainty can have many root causes. Wherever it stems from, it is not only a symptom of an imbalance. It has its own impact.

Target Corp.’s CEO, for example, expects higher prices on fruits and vegetables within days. Gasoline prices could rise, especially in the Midwest, which is dependent on oil from Canada that is now subject to a 10% tariff. Anticipated price increases have already soured consumers.

A Morgan Stanley survey published Wednesday showed the first negative reading of consumer sentiment since last June. Wall Street’s bellwether S&P 500 has fallen more than 5% in two weeks as the tariffs have taken hold. And economists in recent days have been busy reducing their U.S. growth forecasts for the year.

“Every country has seen a surge in uncertainty from the Trump effect,” Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford University economist, writes in an email to the Monitor. “Trump is a one-man uncertainty machine.”

Current doubts include questions around whether a global trade war will ensue, whether Mr. Trump’s policies will encourage multinational companies to invest in the United States or not, and whether his federal workforce downsizing could spark a recession.

When the future looks especially cloudy, firms delay expansions and put off hiring. People buy fewer big-ticket items, such as cars and washing machines. Such fears can slow the economy even beyond the direct effects of higher prices from tariffs.

Echoes of pandemic woes

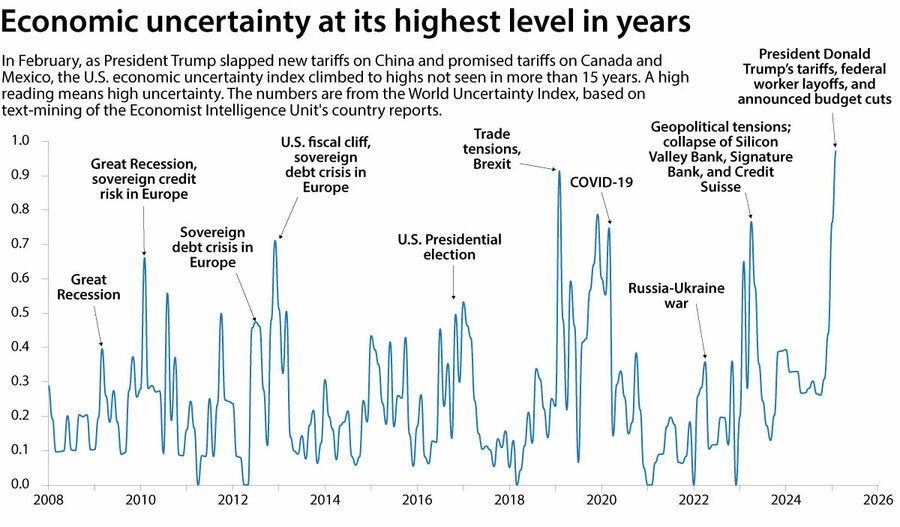

That’s what happened after the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic. According to a 2022 study cowritten by Mr. Bloom, uncertainty surged, as measured by the World Uncertainty Index, and growth slowed. Currently, worldwide uncertainty is surging again toward record levels set during the pandemic. In the U.S., it’s already there.

Mr. Trump’s challenge is that if he slows the economy, it’s not so easy to rev it up again. The chill caused by heightened uncertainty tends to linger. The 2022 study found that its full impact hit two years after the initial surge.

Such a slowdown doesn’t necessarily mean a recession. Earlier this week, Torsten Slok, chief economist for Apollo Global Management, forecast that annual growth would slow about half a percentage point due to the tariffs on Mexico, Canada, and China that took effect Tuesday.

On Wednesday, at the request of several of the nation’s largest automakers, the White House said that those whose cars were imported through the 2020 U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement would qualify for a 30-day reprieve from tariffs. Even so, if Mr. Trump continues to pile on more or higher tariffs in the following months, as he has promised, the slowdown will be even more severe, economists say.

Bracing for impact

The reality, though, is that no one knows what the effects will be. It’s been 90 years since the Hoover administration imposed such broad tariff hikes, which led to retaliatory tariffs by America’s trading partners and, many historians believe, worsened the effects of the Great Depression.

Another big unknown is how those trading partners will react this time. If they impose tariffs of their own, U.S. growth will slow further. That’s because exporters will also see reduced business as foreign tariffs rise, and their foreign markets will likely shrink.

That’s already happening. Canada has announced retaliatory tariffs; Mexico plans to issue its response on Sunday.

On Tuesday, when China retaliated against new U.S. tariffs with tariffs of its own and a halt to all log imports from the U.S., Leigh Allen was ready. The owner of American Log Handlers and Forest to Floor, Mr. Allen had already been burned by Mr. Trump’s trade war with China during his first administration. So, he shifted to selling logs and lumber to factories in Cambodia and Vietnam instead of in China. He also began sourcing more of his hardwood flooring, which he sells in the U.S., from domestic manufacturers rather than from Asian ones.

Still, the current tariffs are troublesome, he adds.

The price for lumber and logs in the market will fall as demand from China decreases, he says. “It puts a stop or a chill on all investment and a stop or a chill on all hiring.”

Tariff proponents point out that during the first Trump administration’s trade wars, the value of the dollar went up. If that happens again, it could help mitigate the price shock of tariffs for consumers. They can use fewer dollars to buy more foreign goods. But it also means that U.S. exporters’ goods are that much more expensive – and less competitive – when sold abroad.

How long will this be going on?

Another uncertainty: how long the tariffs will last. If it’s for a short time, many companies can absorb the price increases, and the economic damage will be limited.

But the longer tariffs last, the more that protected U.S. industries will depend on them as insulation from foreign competition, and they will then lobby for them, says Kyle Handley, director of the Center for Commerce and Diplomacy at the University of California, San Diego. “It’s hard to get rid of protection once you put it in place.”

Despite these concerns, Mr. Allen of American Log Handlers remains upbeat. “I look for opportunity in disruption,” he says.

Staff writer Jacob Posner contributed to this story.