On a mid-February morning, Nicole Moore rolls up to a rented storage unit. The closet-sized room serves as a go-between, its contents connecting her family’s past and present lives.

Her grandmother’s china? A treasured keepsake, now broken and tinted black.

Several donated bicycles? Generosity in the aftermath of a disaster.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Wildfire turned vibrant Altadena to rubble. The Monitor is following what comes next on one block: how neighbors rebuild, how communities change, and how resilience appears in the aftermath of disaster. This is the first installment.

Burned film canisters and a large scroll of paper? Items representing their semipaused professional lives.

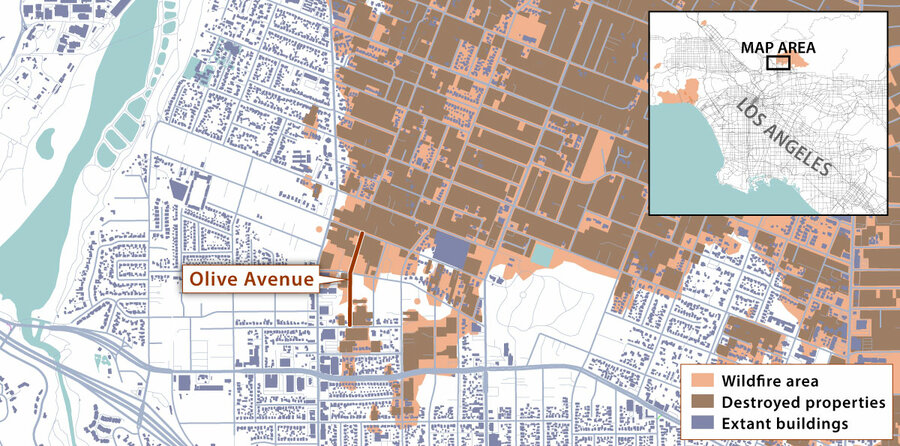

Ms. Moore; her partner, Lorna Green; their 16-year-old daughter, Umalali; and their two dogs are among the thousands of Southern California families whose lives were upended by devastating wildfires this January. The Eaton wildfire, one of two that engulfed neighborhoods in Greater Los Angeles, tore through their beloved 808-square-foot house on Olive Avenue, leaving rubble and a charred oak tree in its wake. Hurricane-level winds carried embers into their Altadena community, burning block after block after block. Seventeen people died in that fire, and officials estimate the blaze destroyed more than 9,400 structures.

A month later, Ms. Moore and Ms. Green are in the initial phase of natural disaster recovery. They’re navigating the emotions and logistics alongside their tight-knit block of neighbors, all of whom have been thrust into a situation beyond the scope of their wildest imaginations. Wildfires, they believed, were never supposed to burn this far into suburbia. They are on the first step of a postdisaster voyage increasingly familiar across the United States, from Asheville, North Carolina; to Fort Meyers, Florida; to Colorado’s Boulder County. It’s a journey the Monitor plans to follow on Olive Avenue.

For the Green-Moore family, gone are the rhythms of the life it had built over the course of two decades, along with almost all of its belongings. No photo albums. No furniture. No African artwork. Not even a toothbrush or a spoon.

“All those things are tied up in routines,” Ms. Moore says.

A two-bedroom Pasadena apartment has replaced their nearly 100-year-old house. This is their new home, or at least a temporary shelter. Their neighbors – the people who would congregate around a red picnic table in their old front yard – are grappling with the same sense of unfamiliarity paired with uncertainty. One has parked a trailer on his debris-filled lot. Others have fanned out to rental properties beyond the borders of Altadena, their melting pot community known for its diversity and artistic flair.

Rebuilding is the goal, Olive Avenue residents say, but big questions obscure the future. How long will that take? Will their insurance payout cover the cost? And will their close-knit neighbors be geographically reunited?

In the meantime, grief overlaps with paperwork and phone calls. Their paying jobs have taken a backseat to their new job: navigating life after being displaced by the wildfire.

Ms. Moore rests her phone on the floor of the storage unit. The speakerphone is on. She’s technically participating in a Zoom meeting for Rideshare Drivers United, an organization she helps lead as president. In her prewildfire life, she drove for Uber on the side. It supplemented income from her job on a health care process improvement team for Los Angeles County.

“I wish I knew what they were saying,” she says while foraging in the storage unit. “It’s too intense for me.”

Ms. Moore gathers supplies, including a shovel with a handle melted during the inferno, for excavating their Altadena property. Time is of the essence. A few days from now, she will return full time to her county job.

Day Zero

Everyone has a Day Zero story.

On Jan. 7, the day the fire started, the Santa Ana winds were howling. Electricity was flickering. It didn’t immediately worry the Green-Moore family, who had experienced nearby wildfires in the past.

“Eaton Canyon is a big, long canyon,” Ms. Moore explains. “Nobody expects it to be the Altadena fire.”

They went to Costco to buy snacks for one of Umalali’s upcoming basketball games. Then the trio stopped at a Vietnamese restaurant. That’s when Ms. Moore’s phone kept dinging with alerts from an app tracking the Palisades and Eaton fires. The fire danger seemed to be creeping ever so close to Lake Avenue, a major north-south thoroughfare cutting through the city.

The couple and their daughter left with their food in boxes and headed back to Altadena. No evacuation orders had been issued for their racially diverse neighborhood. But they decided they would leave for a night or so, mostly out of air-quality concerns for Ms. Green’s mother, Evelyn Sheppard, who was just a block away – and unaware of the inferno visible from her bedroom window. Her fire alarms hadn’t gone off.

“What are you doing here?” Ms. Sheppard asked when they knocked on her apartment door.

With no power or first responders available to assist, they helped Ms. Sheppard down three flights of stairs in the dark.

Before heading to a downtown Los Angeles hotel, they briefly swung by their house. In went the newly purchased snacks and out came a few essentials. Ms. Moore grabbed her work computer and one of Ms. Green’s laptops. Umalali snagged some cosmetic items. They couldn’t find their cat, Lil Man, who lived mostly in their garage-turned-home-office. The winds, they assume, had scared him into hiding.

The four left, with the two dogs in tow, thinking they would return the next day.

Instead, on the morning of Jan. 8, their neighbor, a man they dubbed the “mayor of Olive Avenue” because of his genial spirit and helpful nature, called. Overnight, Jose Castillo told them, their home had burned. So had almost every other house on the street and blocks around them.

Ms. Green and her mother sobbed inside the hotel room. Ms. Moore and Umalali wept on a downtown street while walking the dogs.

Lil Man, they would later learn, wound up at an animal shelter. He perked up when they reunited, devouring a bowl of food and water, but his injuries were too severe. They had to say goodbye to him, too.

The first month

Ms. Green and Ms. Moore describe the initial month after the blaze as a blur punctuated by a series of alarms.

There was a $900 Target shopping trip to grab the bare necessities. There was Federal Emergency Management Agency paperwork to submit. There were insurance calls to make. There were friends and neighbors to check in on. And there was the hunt for a new place to live.

Thousands of similarly displaced families were heeding the same to-do list and flooding potential rental properties. The landlord of one home they tried to rent increased the cost by 10% at the last minute, rendering it unaffordable. As a gay couple and Black-identifying family, Ms. Green and Ms. Moore say the odds are stacked against them. Ms. Moore, who is white, would enter prospective rentals by herself first as an attempt to dodge any potential discrimination. Ms. Green and Umalali, who are Black, would follow.

Eventually, the search concluded. Their new Pasadena apartment is farther from their old neighborhood and Umalali’s school than they would like. But they’re grateful for a stable roof over their heads. At this moment in February, the family of Umalali’s best friend, Hope Gardner, still hasn’t found a new place. The couple often help shuttle Hope back to the Motel 6, where she, her two sisters, and her parents are living.

“We’re very lucky – very, very lucky,” Ms. Green says.

They are not homeless and, thanks to the kindness of friends, never had to stay in the convention center that became a place of last resort for many before securing their apartment.

Now, they pluck their shoes from a cardboard box and take their dogs, who are suddenly without a backyard, to a park. It’s a new routine that doesn’t quite feel familiar. On this morning, Ms. Green forgets her cellphone in the apartment. She chalks it up to change.

“So, are you rebuilding?”

By this crisp February morning, Ms. Green arrives at the senior apartment complex where her mother lives. It’s a block from their former home in Altadena. The building survived, but living in a fire-ravaged zone poses its own challenges. Before her mother could move back in, they needed to scrub a layer of ash blanketing the interior of her apartment.

“Where do you want me to put the water?” Ms. Green asks.

“Under the table,” Ms. Sheppard says.

Residents had received a letter the day before, Feb. 10, warning them that they cannot use tap water for cooking or drinking. Initially, disaster relief organizations dotting the city were donating food and water. Then as the days and weeks passed, help started drying up, Ms. Green says. But danger persists. So they bring her mother water on an almost daily basis.

Ms. Green sinks into a kitchen chair to rest for a moment. Across from her, old family photos decorate a wall. They are the only ones left.

Grief hits Ms. Green in quieter moments. She sometimes finds herself crying behind closed doors in the bathroom. Finding time – and mental space – to dive back into work projects has been difficult. She is a filmmaker, director, and writer, who lost scripts and footage in the fire.

Her partner has been processing the trauma through words. Ms. Moore started writing occasional Facebook posts, chronicling their wildfire experience and retelling older family stories lost in journals turned to ash.

Umalali says she hasn’t shed too many tears, aside from the moment she learned her childhood home was destroyed. She reasons this is because of her age. Not as much sentimental attachment to belongings.

“I can accept that this is gone,” she says, while looking toward the ruins of their house. “And what comes next has to be better.”

What comes next is the topic of conversation when Ms. Green runs into a neighbor on this Tuesday afternoon. Victor Amador wraps her in an embrace on Olive Avenue.

The four words that come next are loaded with emotion.

“So, are you rebuilding?” Ms. Green asks.

“Yes, ma’am,” Mr. Amador says without hesitation. “Are you?”

She nods. He smiles.

“Very good, because you are our family and neighbors,” he replies.

“All your equity is up in smoke”

They know the path to becoming physical neighbors again is anything but straight.

It’s unclear how long it will be until officials give the all-clear to rebuild. A two-part process is under way, with the Environmental Protection Agency first removing hazardous materials from burned properties. In the second phase, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will conduct a federally funded debris cleanup on each plot. County officials have not offered a timeline for overall completion, other than noting that phase two may take two to three days per property.

And then there are the financial considerations.

Ms. Green and Ms. Moore paid $365,000 for their two-bedroom home in 2005. They expect to receive about $310,000 from their insurance to rebuild. How much will it cost per square foot to do so? No one knows.

“All your equity is up in smoke,” Ms. Moore says.

Insurance also pays what’s known as “additional living expenses.” It’s a sum of money intended to offset costs, such as rent, for homeowners with a covered loss. The Green-Moore family is using that money, at least for the next year, to pay for their $4,200 monthly rent.

Slowly but surely, that blank-canvas apartment is blooming with personality. Friends have donated goods to start furnishing their new place. So have strangers. A lamp, salt and pepper shakers, and a stained-glass window decoration? All from an estate sale that morphed into a giveaway event for people displaced by the fires.

“Now we have someone else’s precious things,” Ms. Moore says.

A treasure from the ashes

They haven’t called off the search for their own precious things, though.

Ms. Green sits on a remnant of a front-yard fence, staring at the ashy remains and twisted metal occupying their home’s former footprint. When squirrels scale the giant tree towering over the property, a crispy sound wafts from the singed bark. An arborist told them it has a 50/50 chance of surviving.

“Look at how massive that tree is,” she says wistfully. “It really is a great tree.”

Nearby, Ms. Moore slides her legs into a white hazmat suit. Next comes a breathing mask that filters out particulate matter created by the wildfire. Finally, she slips on hardy gloves.

There’s no longer a door, or even a front porch, but Ms. Moore enters where she thinks those once stood. She points to the living room, kitchen, and two bedrooms – now just debris piles.

She pulls what are likely address labels from a nearly unrecognizable filing cabinet. They dissolve into ash in her hands.

“You have to kind of move forward,” she says. “You can’t just do this for the rest of your life.”

And yet, Ms. Moore shovels and sifts, plucking earring fragments and other disfigured objects as she goes. It’s too soon to say what she will keep or what she will do with the charred mementos.

A visitor interrupts her quest. Their neighbor, Mr. Castillo, air knocks at the nonexistent door.

“Come on in,” she says, laughing. “The door is open.”

Ms. Moore tells him she is ready to give up. She can’t find her partner’s diamond commitment ring. Ms. Green wasn’t wearing it the day they evacuated.

Without being asked, Mr. Castillo grabs a shovel and starts digging. He demonstrates the sifting method he perfected while excavating his own homesite across the street. He finds something resembling a ring.

“Finders keepers,” Mr. Castillo jokes, before stumbling onto more treasure. “Here’s another one! Here’s another one! Here’s another one!”

Ms. Moore peers into his sifter. She spots a ring with what appear to be little diamonds on the band.

“That’s it!” she shouts, as Ms. Green watches from the front yard.

A second later, Ms. Moore eyes damaged dangly earrings in the sifter and shows them to Ms. Green.

Mr. Castillo laughs.

“We all say the same thing,” he says. “‘Do you remember this?’ That’s all we’ve got – memories.”

And for a moment, this neighborly interaction, like dozens before it in simpler times, lightens the mental load. His job done, Mr. Castillo heads home, which is now a trailer parked among the ruins of his fire-ravaged house.

“Thanks so much, Jose,” Ms. Moore says. “That was awesome. You gave us hope.”