The UK is increasingly vulnerable to the threat of missiles and drones after decades of cost-saving cuts eroded its once world-class air defences, military sources and Cold War veterans have warned.

Defence chiefs are understood to be exploring options to regrow Britain’s ability to protect critical national infrastructure – like power stations, military bases and government buildings – from the kind of Russian cruise and ballistic missile strikes that are devastating Ukraine.

But any credible “integrated air and missile defence” plan will cost billions of pounds and would likely require a further increase in defence spending beyond a proposed rise to 2.5% of national income recently announced by the prime minister, according to defence sources.

“Can the UK defend its cities from the skies if there was a barrage of missiles? No,” a senior defence source said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“Do the public know what to do in the event of an air attack? No… Put simply, are we defended? No.”

As part of a series called Prepared For War? Sky News visited air defence sites that once played a key role in protecting Britain during the Cold War – and spoke to veterans who were part of the force that had been on alert to respond to any Soviet air threat.

Pressing the big red button

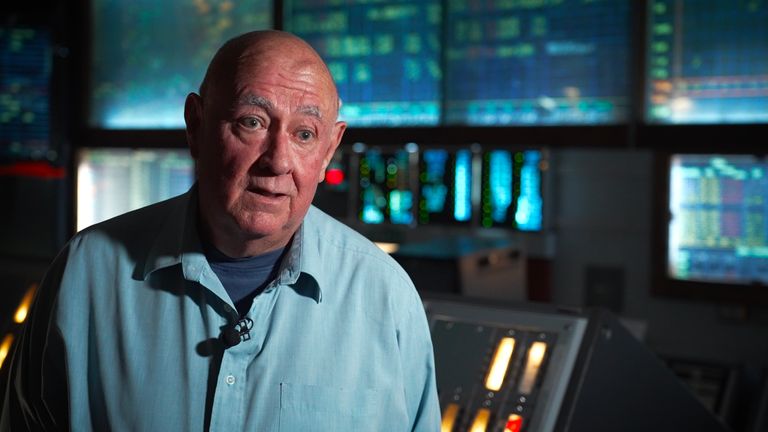

Flicking a line of switches to prime a simulated batch of missiles from inside a cabin at an old military-base-turned-museum in Norfolk, a former Royal Air Force technician watches a screen as a radar scans for enemy aircraft.

“It’s picked up a target,” says Robert Findlater, pointing at a dot on the monitor, which looks more like a retro computer game.

A beeping noise indicates the signal from the radar is becoming stronger as the hostile aircraft approaches.

Once in range, red letters on one of the screens that had read “hold fire” switch to the words “free to fire”, written in green.

Mr Findlater leans forward and presses a big red button.

Suddenly there is a roar as the simulated noise of a missile blasting off shakes the cabin.

The Bloodhound air defence missile, powered with a Rolls Royce engine, could reach 60 miles per hour in a tenth of a second before rocketing up to twice the speed of sound as it powered towards an enemy aircraft or missile – state-of-the-art technology in its day.

“We’ve been successful in our launch,” the RAF veteran says, with a smile.

He then peers back at the screen, watching a line of what looks like radio waves jumping up and down, until there is a spike to indicate the missile closing in on the target.

“It [the radar] is now looking for the missile, and there she is in the beam. Next thing you see – that’s the warhead.

“It’s gone off, and you killed it,” the veteran says, finishing the simulation.

Long retired, Mr Findlater joined the RAF in 1968.

He rose up through the ranks to become chief technician on a Bloodhound unit, charged with ensuring the missiles were ready and able at all times to fire at any threat.

Stepping outside the cabin, from where the system was operated, to a patch of grass, the veteran showed Sky News around the actual weapon – a lethal-looking collection of rockets and warheads, painted white and lying horizontal now, rather than pointing towards the sky.

Asked what message it had been designed to send to NATO’s former Warsaw Pact foes, Mr Findlater said with a chuckle: “Don’t come knocking… It says we’re ready for you.”

The ground-based systems, which had been dotted around the UK’s coastlines, used to be part of a layered grid of Cold War air defences that also included fighter jets and other weapons.

But the entire arsenal of Bloodhound air defence missiles was taken out of service after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, while air bases and fast jet squadrons were reduced to save money as successive prime ministers took what has been described as a “peace dividend”.

There had been talk at the time of investing in US-made Patriot air defence systems – an even more capable piece of kit that remains a core part of the air defences of the United States and a number of other NATO allies.

“But I think the government just gave up and shut everything down because there was no threat any more,” Mr Findlater said.

Asked whether he thought the UK was well defended now, he said: “I don’t feel we’re defended, no, not at all.”

As for how that made him feel, he said: “Sad… Considering what we had in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Frozen in time

Also at the RAF Air Defence Radar Museum is an old Cold War operations room – frozen in time, with giant boards along one wall, charting the number of fighter jets once ready to scramble.

There are also rows of desks, fitted with radar screens and important-looking buttons.

John Baker, 69, once worked in this hub as an aircraft identification and recognition officer.

Asked if the UK’s air defences had been prepared for war back when he served, he said: “We practised. There were exercises for war.

“Every couple of months or so there would be a small exercise and once or twice a year there would be a major NATO exercise in which this – because this radar site was closest to Europe – would be the epicentre.”

While cautioning that he was no longer up-to-date on the military’s air defence capabilities, he sounded less certain about whether they could handle a major attack today.

Click to subscribe to the Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

“If hundreds and hundreds of drones and cruise missiles were to come in. I don’t think we could safely take out all of them,” Mr Baker said.

He added: “I’m glad I did my time back then – and not now.”

Air defences ‘woefully inadequate’

The UK does have highly capable air defence equipment – just no longer enough of it to be able to protect the vast array of critical infrastructure across the country and also to defend troops deployed on operations overseas.

Making the situation more grave is a growth in the quality and quantity of missiles and drones that hostile states such as Russia, China, Iran and North Korea have developed.

At present, the RAF has just nine frontline fast jet squadrons – including the quick reaction alert aircraft that are at the sharp end of defending against any air threat.

While modern jets – F-35 and Typhoon – are far more sophisticated than their predecessors, the UK had 30 frontline squadrons towards the end of the Cold War.

The Royal Navy’s six Type 45 destroyers are kitted with the country’s only ballistic missile defence systems.

But only three of these ships are “available for operations”, according to a navy spokesperson, including one that is deployed on operations in the Middle East.

On land, the military has around six Sky Sabre ground-based air defence systems – each one able to shoot down multiple missiles.

But at least two of these weapons – almost certainly more – are deployed overseas, and those in the UK only have a very limited range.

Read more from Sky News:

Is the UK preparing for war amid threats of conflict?

‘Hard to imagine how UK could be doing less to prepare’

Jack Watling, a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, called the UK’s current array of air defences “woefully inadequate”.

Britain does benefit from its geography, with a lot of European NATO countries between its shores and Russia.

However, the air defences of many European nations have also been reduced to save money since the Soviet Union collapsed.

“We always hear this argument from the Ministry of Defence that gaps in our own capability are acceptable because we’re part of an alliance,” Mr Watling said.

“It’s a little bit like if you were going round to a ‘bring your own booze’ party and you said: ‘Well, there’s other people coming, so I’m not going to bring any alcohol’.

“If everyone adopts that approach, then there is simply nothing to drink. And when we look across NATO, there is an overall shortage [in air defences].”

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said: “The UK is well prepared for any event and defence of the UK would be taken alongside our NATO allies.

“As part of our commitment to invest an extra £75bn for defence over the next six years, we continue to review potential opportunities to develop our capabilities and modernise air defence across Europe in close discussion with allies and partners.”