DURHAM, N.C. — A traveling exhibit from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum was intended to help churches in Durham, North Carolina, better understand how ordinary people helped the Nazis murder Jews during World War II.

But the exhibit, planned last summer, has now drawn critics who say it highlights the genocide of Jews at a time when it is Palestinians who are facing a murderous campaign that has killed more than 30,000 and left hundreds of thousands without food or shelter.

The flap over the exhibit, now on view at First Presbyterian Church in downtown Durham, is part of a larger reassessment of the Holocaust, the genocide of 6 million European Jews during World War II, and how that event should be remembered and memorialized.

“Having such an exhibit at this time that makes no mention of genocides anywhere else before or since is in my opinion harmful,” said Rinah Rachel Galper, an activist from Durham who is also Jewish and runs an organization called Joyoushout, Supporting Youth and Adult Change Makers.

Galper teamed up with a handful of Christians and Muslims to pressure churches to broaden the exhibit. “We were trying to really provide a deeper context for understanding that it has happened before and since,” she said.

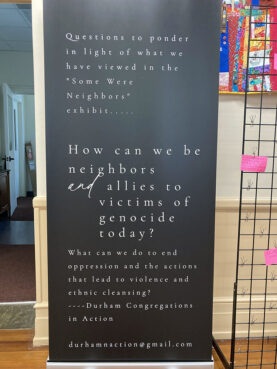

First Presbyterian Church has agreed to accept a banner at the end of the exhibit that asks, “How can we be neighbors and allies to victims of genocide today?” (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

So far, the ad hoc group has been only partly successful. First Presbyterian Church agreed to accept a banner the group produced and paid for that asks, “How can we be neighbors and allies to victims of genocide today?” It also accepted a freestanding metal grid where people can clip notes with their thoughts.

The church rejected two more substantial sets of panels showing genocides around the world, including a map.

A church pastor said the congregation needed more time to review the additional panels.

“Our session approved for us to have this specific exhibit,” said Esther Hethcox, associate pastor at First Presbyterian, referring to the body of elected elders that govern the church. “And so when there were things that were additional to it, and that further a different conversation, that would require a different proposal to the session.”

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibit, “Some Were Neighbors,” a set of 22 posters, has been traveling across the U.S. for the past two years and around the world since 2013. The exhibit, which examines the role of ordinary people in the Holocaust, was on exhibit at two other Durham churches earlier this year as part of an initiative to combat religious hate undertaken by an interfaith group, Durham Congregations in Action.

The memory of the Holocaust, however, has become a particularly vexing issue for Jews in light of Israel’s assault on Gaza, which some are also calling a genocide. Should the Holocaust be viewed as a singular event, unlike anything that has occurred before or after in history, and therefore undeserving of comparisons with any other mass killings or genocides? Or should the lessons of the Holocaust’s “Never Again” be applied to other people groups and not just the Jews?

Earlier this month, British director Jonathan Glazer accepted an Oscar for a movie about the Holocaust and in his speech connected it to the war in Gaza, drawing an analogy between the two.

“All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present — not to say, ‘Look what they did then,’ rather, ‘Look what we do now,’” said Glazer, who directed “The Zone of Interest,” which follows the domestic life of a Nazi commander whose house is just outside the Auschwitz concentration camp. “Our film shows where dehumanization leads at its worst. It’s shaped all of our past and present.”

Director Jonathan Glazer, right, gives an acceptance speech after “The Zone of Interest” won the Oscar for best international feature. (Video screen grab via ABC)

Glazer was pilloried by many in the U.S. Jewish community.

David Schaecter, president of the Miami-based Holocaust Survivors’ Foundation USA and himself a survivor, wrote in an open letter to Glazer that it was “factually incorrect and morally indefensible” to compare the Holocaust with Israel’s actions in Gaza.

“You should be ashamed of yourself for using Auschwitz to criticize Israel,” Schaecter wrote.

Jonathan Greenblatt of the Anti-Defamation League posted to social media that Glazer’s words “minimize the Shoah & excuse terrorism of the most heinous kind.” (Shoah is the Hebrew word for Holocaust.)

Despite these loud disavowals, Israel’s actions in Gaza are increasingly being compared, if not called, a genocide. In January, the International Court of Justice found it is “plausible” that Israel has committed acts that violate the Genocide Convention. It ordered Israel to ensure its troops commit no genocidal acts against Palestinians, after South Africa accused Israel of state-led genocide in Gaza.

Many Jews, especially in Israel, found the ICJ’s provisional order offensive and insist the Holocaust was unique.

In some ways it was, said Raz Segal, a historian who runs the Holocaust and Genocide Studies program at Stockton University in New Jersey. Although genocides took place before the Holocaust — mostly at the hands of colonial powers — the very word genocide was first applied to the Holocaust. The word was coined by Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin who brought together “geno” — from the Greek word for race or tribe — with “cide,” from the Latin word for killing. In 1948, the United Nations adopted Lemkin’s term when it approved the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.

“The crime of genocide really emerges immediately with this idea that the Holocaust is unique, that Jews are unique,” said Segal.

RELATED: A Jew coined the word ‘genocide.’ Now it’s being used against the Jewish state.

Many Jews in Israel still hold onto that view that owing to what happened to them during the Holocaust, Jews are incapable of genocide.

That’s what Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu seemed to suggest after the world court issued its preliminary finding in January.

“The mere claim that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians is not only false, it’s outrageous, and the willingness of the court to even discuss this is a disgrace that will not be erased for generations,” Netanyahu said.

But an increasing number now reject the view that Israel is somehow immune from committing genocide.

“The problem with insisting that no genocide can compare to the Nazi Holocaust forces this conception that Jews are a unique people, and that they are the one people in the world who cannot commit genocide because they’ve been victims of the world’s worst genocide,” said Barry Trachtenberg, a historian who studies the Holocaust at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “By insisting that Jews and Israel are somehow exceptional in this way, it’s just a reinforcement of antisemitic principles that Jews are fundamentally different people in the world.”

Rinah Rachel Galper in Durham, N.C. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

Galper, who joined forces with others in Durham to oppose the Holocaust exhibit at First Presbyterian, shares the concern.

“I would really like my Jewish people to survive, and this is not a good recipe for survival,” she said, referring to an exhibit that privileges Jews, while others, namely Palestinians, suffer terrible oppression.

One of Galper’s collaborators, retired Presbyterian pastor J. Mark Davidson, agreed that the exhibit needs additional information about genocide as a deliberate killing of ethnic groups happening in other times and places around the world.

“On the face of it, there’s nothing wrong with an exhibit from the Holocaust Museum,” said Davidson, who now directs a group called Voices for Justice in Palestine. “But given the timing and the context and the fact that many other communities are being affected, it seemed like a way of privileging one perspective and silencing others.”

Durham Congregations in Action, the group that arranged for the traveling show, was expecting five churches to host the exhibit. One has now backed out.

A sign-up for additional dialogue at the “Some Were Neighbors” exhibit at First Presbyterian Church in Durham, North Carolina. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

“Due to scheduling conflicts, there was not enough time to prepare the congregation to receive the exhibit,” the Rev. Donna Banks, pastor of Epworth United Methodist Church in Durham, wrote in an email.

Breana van Velzen, executive director of Durham Congregations in Action, said some changes to the exhibit could be constructive.

“I’m generally in favor of expanding the exhibit,” van Velzen said. But the decision to do that is up to the churches. “It’s their space and I’m going to respect that.”

The exhibit will remain at First Presbyterian Church until March 22.

RELATED: The anti-Zionist Jews countering mainstream support for Israel