(RNS) — When Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby resigned in November over his failure to report a serial child abuser in his own denomination, the drastic step, it was thought, would preserve the Church of England’s ability to discipline its clergy in other cases of abuse — and its moral authority overall.

Before Welby could leave office, however, the bishop of York, who was to run the Church of England in the interim, was hit with questions about his own management of abuse, and on Jan. 28, the bishop of Liverpool resigned after being accused of making unwelcome sexual advances. (He denies the allegations, saying he resigned so as not to be “a distraction.”)

While the clergy sexual abuse crisis has most famously struck the Catholic Church, every faith tradition and every kind of clergy (though mostly male) have been implicated: celibate monks and Protestant ministers who are family men. In the past five years, three Anglican denominations in the United States and Canada have all been rocked by abuse and misconduct allegations.

Though two — the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada — are members of the Anglican Communion and recognize the authority of the archbishop of Canterbury as their convener, all three have distinct cultures and separate protocols for handling abuse.

“These churches have spent decades attempting to reform their policies and procedures for handling complaints against their clergy and lay leaders, but we see the same kinds of complaints surface again and again from people brave enough to go public,” said Matthew Townsend, a former communications executive with several Anglican organizations who quit because of his dissatisfaction with how abuse was handled.

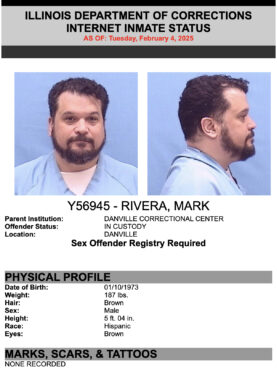

Mark Rivera is imprisoned at Danville Correctional Center in Danville, Ill. (Image courtesy of Illinois Department of Corrections)

In the Anglican Church of North America, which split from the Anglican Communion in 2009 over acceptance of LGBTQ clergy and same-sex marriages, the reckoning with abuse began with a 9-year-old girl who came forward in 2019 with sexual abuse allegations against Mark Rivera, a lay minister in ACNA’s Upper Midwest Diocese who is married with four children. Ten others eventually claimed Rivera abused or groomed them.

Rivera, who served in two churches in the diocese, was convicted of felony child sexual assault in 2022 and later pleaded guilty to felony sexual assault in a case involving an adult. For years, however, the abuse survivors said, those in charge were slow to respond and stood by Rivera even after he was arrested. Stewart Ruch, the bishop of the diocese, has admitted to “regrettable errors” in his handling of the Rivera case and is awaiting a church trial.

At Falls Church Anglican, a historic church in Virginia in a different ACNA diocese, leaders waited 16 years before investigating alleged sexual abuse in the 1990s by a married former youth pastor, or informing the congregation that it had happened, and only after the national church leadership demanded they do.

“The Welby case provides a template for how most churches have responded, unfortunately, that unless there’s outside pressure, no change occurs,” said the Rev. Gerard McGlone, a Jesuit priest and senior research fellow at the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs at Georgetown University. “What we see is what I call a perpetrator-based approach, where the perpetrator and protecting the institution and the reputation of the institution is paramount, as opposed to really walking with those who’ve been most egregiously harmed.”

While conservative denominations are often presumed to be more prone to these shortcomings, experts say abuse knows no theological bounds. Since 2021, two bishops in the Anglican Church of Canada, including Mark MacDonald, a national Indigenous archbishop, resigned due to sexual misconduct allegations. In 2023, Julia Ayala Harris, president of the Episcopal Church’s House of Deputies, the second-highest-ranking officer in the denomination, made public a letter detailing the church’s response to her formal complaint against a retired bishop who, she said, had subjected her to “non-consensual physical contact” and “inappropriate verbal statements.” The church referred the bishop to pastoral counseling.

The Rev. Gerard McGlone. (Photo courtesy of Georgetown University)

Asked why clergy misconduct continues even after the reckoning of #Churchtoo, an echo of the #MeToo movement that brought down movie producer Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby and others, McGlone cited the concept of “acquired situational narcissism.” When they assume influential roles, clergy, like other celebrities, can experience a new sense of power that distorts their perceptions and impacts behavior. Theologies that paint clergy as the “voice of Christ” can exacerbate this dynamic.

Parishioners tend to buy into clergy’s status. “I think there’s a lot of default trust in pastors or other clergy who have success in one way,” said a former parishioner of The Church of the Resurrection, an ACNA church in Washington, D.C., who filed a complaint alleging the rector, the Rev. Dan Claire, had been spiritually and emotionally abusive. “Because they have some people who think they have good character, that doesn’t mean that they’re not treating others in a way that is lacking in integrity.”

McGlone, a survivor of childhood clergy sexual abuse who has authored several sexual abuse prevention programs, added that churches often fail to see themselves as “high-risk organizations,” where those in power are serving children and vulnerable adults. High-risk settings, he said, require outside accountability to become highly reliable.

Townsend, the former ACC and Episcopal Church employee, said the danger of abuse is present whenever humans congregate, but especially so in churches. “The spiritual intimacy of churchgoing is a major component of that heightened danger, and it is not one that is diminishing as Anglicanism declines,” he said.

The decline of church attendance in the United States may contribute as well. “Across Anglicanism, the groups are smaller, more stressed, and more closely knit. They’re tired and they’re afraid of losing what they love. Threats will be viewed with contempt, even and especially when they come in the form of a survivor seeking restitution.”

Denominations like ACNA, the Episcopal Church and ACC are also relatively small. The largest, the Episcopal Church, has just over 1.5 million members. (American Catholics, by comparison, number over 50 million.) The leaders in these Anglican bodies know each other well, and camaraderie among clergy can create barriers to accountability.

In the Episcopal Church, former Presiding Bishop Michael Curry and Bishop Todd Ousley, a former Office of Pastoral Development official, faced internal investigations after reportedly failing to initiate proper disciplinary proceedings against Prince Singh, a fellow bishop in Michigan, when Singh was accused by his family of alcoholism and physical and emotional abuse.

The Rt. Rev. Prince Grenville Singh, former provisional bishop of the Episcopal Dioceses of Eastern and Western Michigan, in December 2022. (Video screen grab/Episcopal Diocese of Western Michigan)

In December, the denomination announced that Singh, who resigned his bishop’s post in September 2023, would be suspended for at least three more years and can only return to ministry at the presiding bishop’s discretion. Curry and Ousley agreed to write apologies, and Ousley, previously the point person on misconduct claims against bishops, was required to undergo training. Days later, the Diocese of Wyoming nominated Ousley to serve as provisional, or interim, bishop.

“Ousley is being allowed to fail upward as if nothing happened,” said Heather Griffin, an anti-abuse advocate who has worked with survivors of abuse in both the ACNA and the Episcopal Church.

Episcopal polity gives the national church more power over bishops and their dioceses, but the more-decentralized ACNA and ACC allow bishops more autonomy, including in enforcing abuse protocols in their dioceses.

In a November 2024 letter, acting Primate Anne Germond — the convening bishop of the ACC — said abuse allegations are “not within the purview of the Primate.” According to the Rev. Martha Tatarnic, rector at St. George’s Anglican Church in St. Catharines, Ontario, this delegation of responsibility to other, less central church bodies means there’s no effective mechanism of accountability when bishops mishandle abuse allegations in their diocese.

“In the ACNA system right now, the bishop is expected to meet with the victim, make credibility determinations, conduct investigations personally,” said the Rev. William Barto, a priest in an ACNA subjurisdiction called the Reformed Episcopal Church. “Until the bishops let go of their centrality in this process, and empower others to process complaints, adjudicate the facts and maybe sometimes even determine the sentence, it’s going to be clunky.”

Even when protocols are enforced, they are often botched, in part because, as Barto noted, the disciplinary process is “amateur-oriented,” run by clergy and volunteers.

In 2020, several parishioners submitted spiritual abuse and misconduct allegations against Claire, the rector of The Church of the Resurrection. After a failed investigation, a second, by an outside firm, advised the diocese, The Diocese of the Mid-Atlantic, to reassess the claims against Claire. Instead, in June, the diocese announced Claire had apologized to the remaining complainants and “has the confidence of the bishops of this diocese.” Bishop Steve Breedlove, who oversaw the initial botched investigation, also issued a public apology for the “long, painful, and misguided” process.

“Nobody can make a godly decision from a place of fear. But that seems to be a major driver in all their decision making,” said a second former parishioner who filed a complaint against Claire. “Who will bear the consequences instead? The victims.”

Dissatisfaction with all three denominations’ procedures has led grassroots advocacy groups to call for changes, with some effect on policy. This summer, the Episcopal Church adopted more than 20 resolutions related to church bylaws governing clergy abuse or misconduct. The ACNA has established minimum requirements in its misconduct protocols that dioceses must adopt by the end of 2025, though a hoped-for overhaul of the clergy misconduct policy was stalled.

Since then, ACNA’s new archbishop, Steve Wood, called for an updated proposal on abuse protocols that could go before Provincial Council in summer 2026. While some celebrated the changes, updating protocols is only part of the solution, say survivors. Until the culture of their churches learns to prioritize parishioners for themselves, survivors say, safety will be elusive.

“You’ve got to find and you’ve got to walk with those who are already walking the walk,” said McGlone of abuse survivors who’ve found fellowship and healing with one another amid their hurt. “And those are the survivors.”