(RNS) — For years, studies have suggested that many white evangelical Christians reject the scientific consensus that human actions are driving climate change.

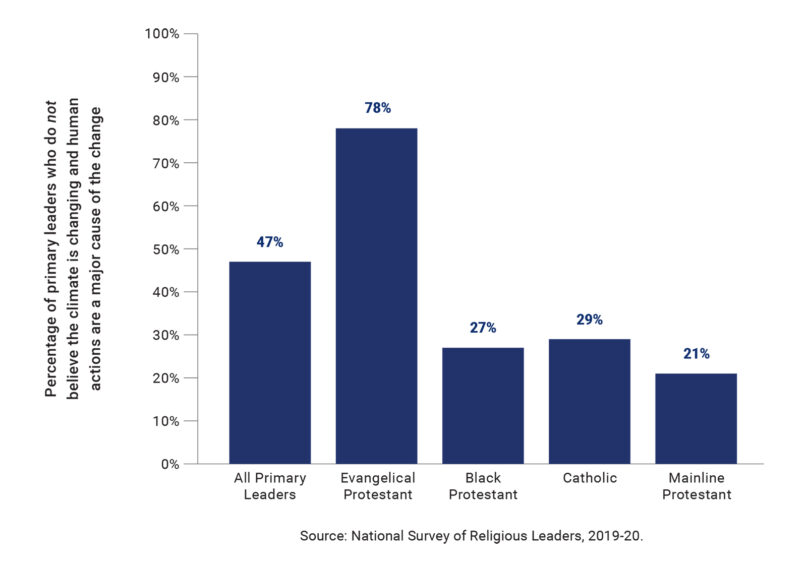

A just-published study of clergy in America confirms it. According to the National Survey of Religious Leaders, 78% of white evangelical clergy reject the assertion that human actions are the cause of climate change. By contrast, only 27% of Black Protestant clergy and 21% of liberal or mainline Protestant clergy reject it.

The study of 1,600 U.S. congregational leaders across the religious spectrum was conducted in 2019 and 2020, and some findings have been released over the years, but the entire report was just published.

It finds that while white evangelical clergy reject the idea that humans are responsible for climate change, they are not always anti-science.

“I think there’s very little reason to think anything’s changed much in the last five years,” said Mark Chaves, the study’s principal investigator and a professor of sociology at Duke University.

By contrast, most clergy, including white evangelicals, endorsed a medical approach to treating depression in addition to a spiritual approach. The study found that 87% of evangelical clergy said they would encourage their congregants to seek help from a mental health professional when suffering from depression. (85% of Black Protestants, 97% of mainline Protestants and 99% of Catholics agreed.)

“Percentage of primary leaders who do not believe the climate is changing and human actions are a major cause of the change” (Graphic courtesy of National Survey of Religious Leaders)

“Clergy overwhelmingly adopt either a wholly medical or a combined medical and religious view of depression,” the study concluded.

Likewise, 69% of all clergy, and 64% of white evangelicals in particular, endorse palliative care at the end of life, agreeing that in some circumstances, patients should be allowed to die by withholding possible treatments, suggesting an underlying support for a medical science approach.

The contrast between the two views of science — the rejection of climate science but the acceptance of medical science — is striking. And researchers suggest one motivating factor: politics.

“Differences among clergy about the more recent issue of climate change suggest a connection to partisan politics more than to theology,” said Chaves.

Mark Chaves. (Photo © Duke University)

White evangelicals overwhelmingly vote Republican — Donald Trump won the support of about 80% of white evangelical Christian voters in 2016, 2020 and 2024, according to AP VoteCast — and the Republican Party has become steadfastly opposed to any policy reforms on climate change in recent decades.

When it comes to climate change, white evangelicals may be driven by their politics more than their religion. Republicans, at least prior to the pandemic when the study was fielded, have not been steadfastly opposed to medicine — which may be one reason evangelicals are more likely to accept it.

“It used to be the thinking that religion always came first and people’s religious commitments drove their politics,” said Chaves. “There’s been more recognition lately of how it goes in the opposite direction, and this is kind of a version of that too.”

Robert P. Jones, the president of Public Religion Research Institute, agreed.

“Climate change has been politicized in a way that mental health has not,” Jones said. “So it’s not that (evangelicals) don’t believe in climate science and they do believe in the science behind medications and psychological counseling. It’s that rejecting climate change has been established as a necessary tribal partisan belief in a way that rejecting mental health treatment has not.”

The National Survey of Religious Leaders, though fielded before the coronavirus pandemic, offers a detailed picture of the country’s clergy with demographic data on clergy age, sex, congregation size, compensation, health and well-being. It is considered the largest, most nationally representative survey on clergy available.

RELATED: Protestant denominations try new ideas as they face declines in members and money

It found that in 2019-20, the median primary congregational leader was 59 years old, seven years older than the median clergy age of 52 in a similar 2001 survey. Most U.S. clergy of all faiths (66%) found their calling as a second career.

Women accounted for only 17% of congregations’ primary leaders, though up from 11% in 2001 when a similar study of clergy was published. Most of those women clergy leaders were concentrated in liberal mainline traditions; 32% of those churches are led by women.

Among the clergy leading congregations (890 of the 1,600 surveyed), 66% were white, 26% Black, 5% Hispanic and 3% Asian. Catholic priests were the most diverse racially, with 21% who were Hispanic.

The median primary clergy leader was paid $52,000 for working full time; 7% of full-time primary clergy earned $100,000 or more, while 20% earned less than $35,000 a year. Most congregations no longer provide their leader with housing. Only 21% reported that they lived in a manse, parsonage or rectory, a drop from 39% in 2001.

U.S. clergy are pretty happy and physically healthy. Only 5% of clergy said their health was poor or fair, compared with 12% in the general population, according to a Centers for Disease Control study. Mainline clergy were somewhat less happy and satisfied in comparison with other religious traditions.

Finally, busting the perception that clergy are overworked and burned out, the survey found that 97% of clergy were very or moderately satisfied with their work, and 85% felt satisfied with their life almost every day. (The survey was conducted before the coronavirus panedemic, and some studies post-pandemic have shown an increase in clergy burnout and stress.)

“The overall picture is that clergy who lead congregations are generally happy and satisfied with their lives and work,” the report concluded. Liberal congregational leaders were somewhat less happy. Only 78% said they feel satisfied with their life every day.

The survey, funded by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, had a margin of error of 3.5 percentage points.

RELATED: Are white evangelical pastors at odds with their congregants? A new study says no.