Plastic is nearly everywhere.

Scientists have detected microplastics from the peak of Mount Everest and the depths of the Marianas Trench to the air we breathe and the water we drink.

Why We Wrote This

The rapid growth of plastic pollution is grabbing attention – on Earth Day and in global treaty talks. Our story and charts show the scale of the problem and possible paths toward solutions.

The challenge for humanity, then, is how to clean up our own mess. Hence today’s theme for Earth Day: planet versus plastics.

The prospect of charting a new course is daunting. This week, leaders from around the world are gathering in Ottawa, Ontario, for the fourth of five sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, tasked with designing a global treaty on plastic pollution by this year.

Ideas for better ways of doing things abound, from using more traditional alternatives to adopting new materials. Bioplastics made from biomass – including seaweed derivatives – are often biodegradable. Polylactic acid, made from sugarcane or corn, needs the right temperature and pressure conditions to decompose.

“There is no one silver bullet that is going to solve this problem,” says Erin Simon of the World Wildlife Fund. Using less plastic and improving recycling and waste management systems will continue to be essential. “No matter the technical solution, we need the infrastructure and the policy to go with it.”

The good news she sees is that public opinion is rallying against plastic waste.

Plastic is nearly everywhere.

Scientists have detected microplastics from the peak of Mount Everest and the depths of the Marianas Trench to the air we breathe and the water we drink.

The challenge for humanity, then, is how to clean up our own mess. Hence today’s theme for Earth Day: planet versus plastics.

Why We Wrote This

The rapid growth of plastic pollution is grabbing attention – on Earth Day and in global treaty talks. Our story and charts show the scale of the problem and possible paths toward solutions.

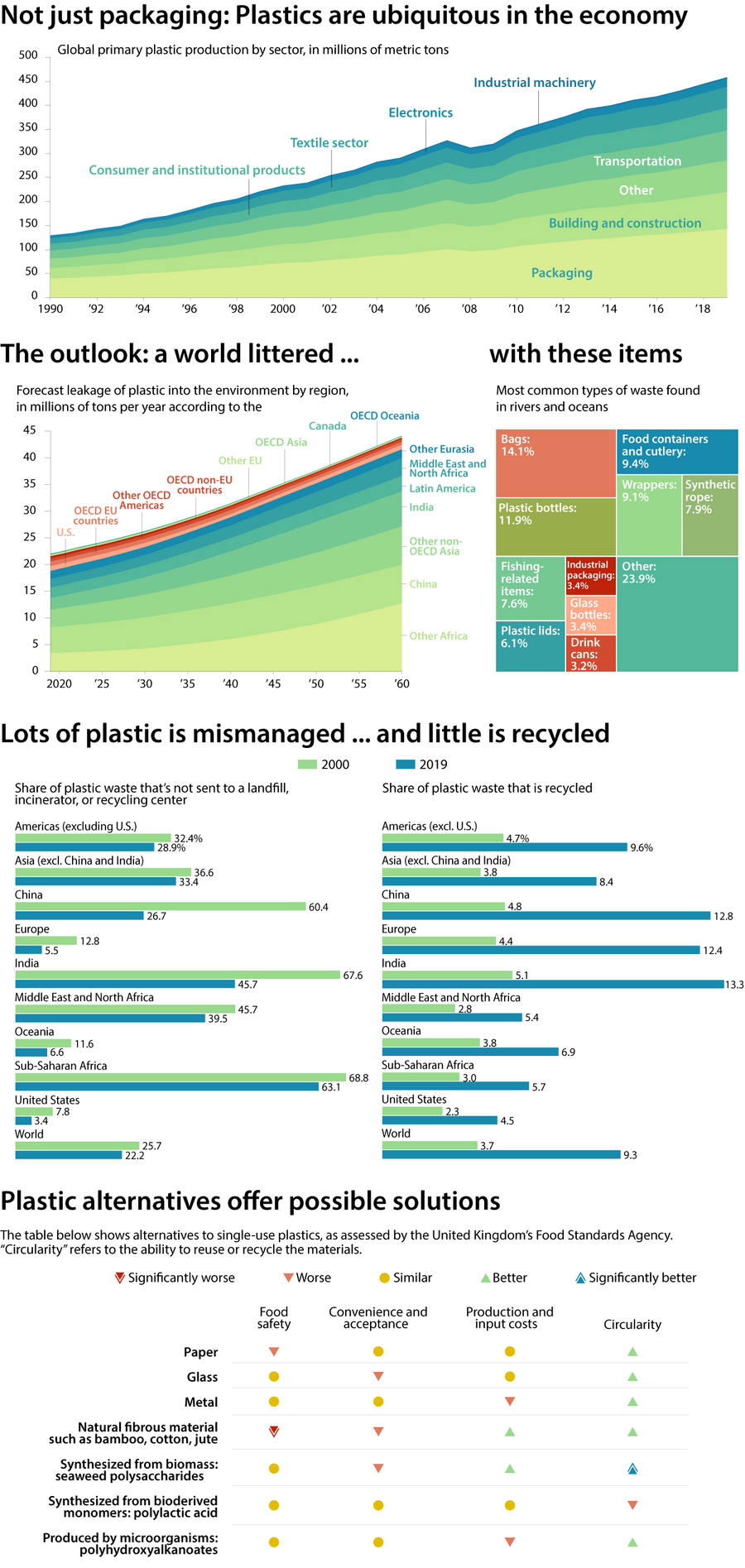

More than 400 million metric tons of plastic are produced each year, using thousands of chemicals scientists believe to be harmful. Plastic waste is expected to triple by 2060. Of the 48 million tons the United States generates, about 5% is recycled, leaving the rest to landfills, incinerators, and pollution. Meanwhile, plastic production accounts for 5% of the world’s carbon emissions and 12% of its oil demand.

The prospect of charting a new course is daunting. This week, leaders from around the world are gathering in Ottawa, Ontario, for the fourth of five sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-4), tasked in 2022 with designing a global treaty on plastic pollution by this year. Already, in the past decade more than 60 nations have enacted some sort of ban on the use of polystyrene foam in things like cups and food packaging.

Ideas for better ways of doing things abound, from using more traditional plastic alternatives such as paper, glass, and metal to adopting new materials. Bioplastics made from biomass – including starches, wax, and seaweed derivatives – are often biodegradable. That’s an important virtue in line with efforts to create a more “circular economy” with sustainability in mind.

Polylactic acid, made from sugarcane or corn, is being used to package fruits, juice, and yogurt, though it needs the right temperature and pressure conditions to decompose.

“There is no one silver bullet that is going to solve this problem,” says Erin Simon, vice president of Plastic Waste and Business at the World Wildlife Fund, one of the world’s leading international conservation organizations. Using less plastic and improving recycling and waste management systems will continue to be essential. “No matter the technical solution, we need the infrastructure and the policy to go with it.”

The good news, says Ms. Simon, is that public opinion is rallying against plastic waste. A global ban on single-use plastics is supported by 85% of people polled around the world, according to a WWF and Plastic Free Foundation survey.

“There are so many things that we can disagree on,” says Ms. Simon. “But on this one, we all agree … There is no plastic that should be in nature.”

For regular people who want to do something, she offers the same advice she gives large businesses: “Clean up your own house. Look at how you depend on single-use,” she says. “Make those choices. Don’t look for perfect. Take one step at a time … Then advocate.”