After a series of lower-paying jobs, Nicole Slemp finally landed one she loved.

She expected to return to her job in Washington state’s child services department after having her son in August. But the best option for child care would cost about $2,000 a month, with a long wait list. The least expensive option was around $1,600, still eating up most of Ms. Slemp’s salary. Her husband earns about $35 an hour at a hose distribution company. Between them, they earned too much to qualify for government help.

Why We Wrote This

Women have reached historic highs in the workforce. But the gap is growing for one group, and lack of affordable child care is to blame. The Education Reporting Collaborative kicks off its series, “Fixing the Child Care Crisis.”

Ms. Slemp, who lives in a Seattle suburb, felt like she had no choice but to quit her job.

That dilemma is common in the United States, where high-quality child care programs are prohibitively expensive, government assistance is limited, and day care openings are sometimes hard to find at all.

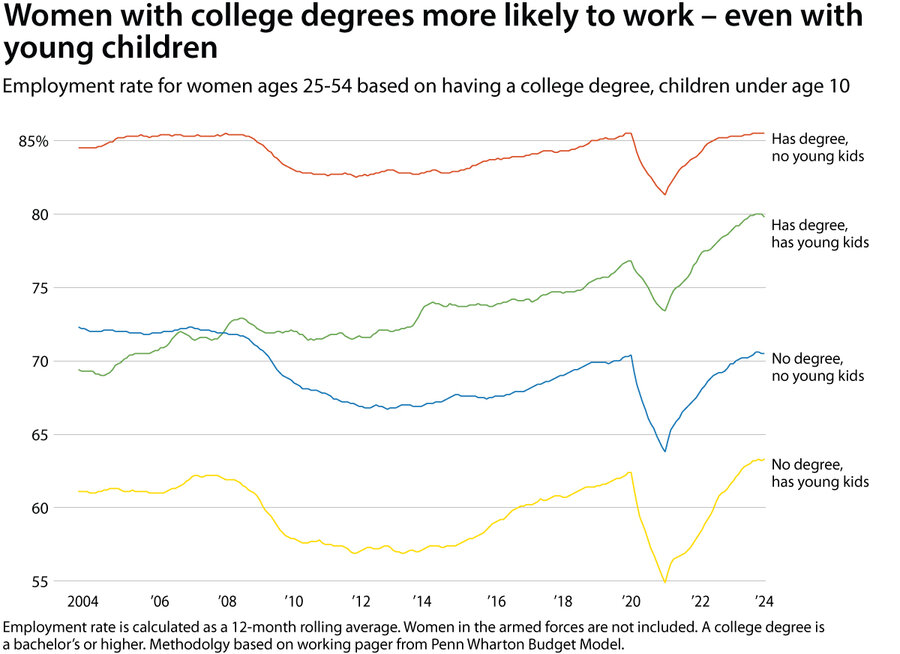

Women’s participation in the workforce has recovered from the pandemic, reaching historic highs in December 2023. But that masks a lingering crisis among women who lack a college degree: The gap in employment rates between mothers who have a four-year degree and those who don’t has only grown.

After a series of lower-paying jobs, Nicole Slemp finally landed one she loved. She was a secretary for Washington’s child services department, a job that came with her own cubicle, and she had a knack for working with families in difficult situations.

Ms. Slemp expected to return to work after having her son in August. But then she and her husband started looking for child care – and doing the math. The best option would cost about $2,000 a month, with a long wait list, and even the least expensive option around $1,600, still eating up most of Ms. Slemp’s salary. Her husband earns about $35 an hour at a hose distribution company. Between them, they earned too much to qualify for government help.

“I really didn’t want to quit my job,” says Ms. Slemp, who is in her 30s and lives in a Seattle suburb. But, she says, she felt like she had no choice.

Why We Wrote This

Women have reached historic highs in the workforce. But the gap is growing for one group, and lack of affordable child care is to blame. The Education Reporting Collaborative kicks off its series, “Fixing the Child Care Crisis.”

The dilemma is common in the United States, where high-quality child care programs are prohibitively expensive, government assistance is limited, and day care openings are sometimes hard to find at all. In 2022, more than 1 in 10 young children had a parent who had to quit, turn down or drastically change a job in the previous year because of child care problems. And that burden falls most on mothers, who shoulder more child-rearing responsibilities and are far more likely to leave a job to care for kids.

Even so, women’s participation in the workforce has recovered from the pandemic, reaching historic highs in December 2023. But that masks a lingering crisis among women like Ms. Slemp who lack a college degree: The gap in employment rates between mothers who have a four-year degree and those who don’t has only grown.

For mothers without college degrees, a day without work is often a day without pay. They are less likely to have paid leave. And when they face an interruption in child care arrangements, their families are far more likely to adjust by giving up work, according to an analysis of Census survey data by the Education Reporting Collaborative.

In interviews, mothers across the country shared how the seemingly endless search for child care, and its expense, left them feeling defeated. It pushed them off career tracks, robbed them of a sense of purpose, and put them in financial distress.

Women like Ms. Slemp challenge the image of the stay-at-home mom as an affluent woman with a high-earning partner, says Jessica Calarco, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“The stay-at-home moms in this country are disproportionately mothers who’ve been pushed out of the workforce because they don’t make enough to make it work financially to pay for child care,” Dr. Calarco says.

Her own research indicates three-quarters of stay-at-home moms live in households with incomes less than $50,000, and half have household incomes of less than $25,000.

Still, the high cost of child care has upended the careers of even those with college degrees.

When Jane Roberts gave birth in November, she and her husband, both teachers, quickly realized sending baby Dennis to day care was out of the question. It was too costly, and they worried about finding a quality provider in their hometown of Pocatello, Idaho.

The school district has no paid medical or parental leave, so Ms. Roberts exhausted her sick leave and personal days to stay home with Dennis. In March, she returned to work and husband Mike took leave. By the end of the school year, they’ll have missed out on a combined nine weeks of pay. To make ends meet, they’ve borrowed money against Jane’s life insurance policy.

In the fall, Ms. Roberts won’t return to teaching. The decision was wrenching. “I’ve devoted my entire adult life to this profession,” she says.

For low- and middle-income women who do find child care, the expense can become overwhelming. The Department of Health and Human Services has defined “affordable” child care as an arrangement that costs no more than 7% of a household budget. But a Labor Department study found fewer than 50 American counties where a family earning the median household income could obtain child care at an “affordable” price.

There’s also a connection between the cost of child care and the number of mothers working: a 10% increase in the median price of child care was associated with a 1% drop in the maternal workforce, the Labor Department found.

In Birmingham, Alabama, single mother Adriane Burnett takes home about $2,800 a month as a customer service representative for a manufacturing company. She spends more than a third of that on care for her 3-year-old.

In October, that child aged out of a program that qualified the family of three for child care subsidies. So she took on more work, delivering food for DoorDash and Uber Eats. To make the deliveries possible, her 14-year-old has to babysit.

Even so, Ms. Burnett had to file for bankruptcy and forfeit her car because she was behind on payments. She is borrowing her father’s car to continue her delivery gigs. The financial stress and guilt over missing time with her kids have affected her health, she says. She has had panic attacks and has fainted at work.

“My kids need me,” she says, “but I also have to work.”

Even for parents who can afford child care, searching for it – and paying for it – consumes reams of time and energy.

When Daizha Rioland was five months pregnant with her first child, she posted in a Facebook group for Dallas moms that she was looking for child care. Several warned she was already behind if she wasn’t on any wait lists. Ms. Rioland, who has a bachelor’s degree and works in communications for a nonprofit, wanted a racially diverse program with a strong curriculum.

While her daughter remained on wait lists, Ms. Rioland’s parents stepped in to care for her. Finally, her daughter reached the top of a waiting list – at 18 months old. The tuition was so high she could only attend part-time. Ms. Rioland got her second daughter on waiting lists long before she was born, and she now attends a center Ms. Rioland trusts.

“I’ve grown up in Dallas. I see what happens when you’re not afforded the luxury of high-quality education,” says Ms. Rioland, who is Black. “For my daughters, that’s not going to be the case.”

Ms. Slemp still sometimes wonders how she ended up staying at home with her son – time she cherishes but also finds disorienting. She thought she was doing well. After stints at a water park and a call center, her state job seemed like a step toward financial stability. How could it be so hard to maintain her career, when everything seemed to be going right?

“Our country is doing nothing to try to help fill that gap,” Ms. Slemp says. As a parent, “we’re supposed to keep the population going, and they’re not giving us a chance to provide for our kids to be able to do that.”

Carly Flandro of Idaho Education News, Valeria Olivares of The Dallas Morning News, and Alaina Bookman of AL.com contributed to this report. Moriah Balingit reported from Washington, D.C., and Sharon Lurye from New Orleans.

This article, the first in the series “Fixing the Child Care Crises,” was produced by the Education Reporting Collaborative, a coalition of eight newsrooms that includes AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, Idaho Education News, The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, and The Seattle Times.