Taiwan goes to the polls this weekend, and the world is watching: The result could influence whether and when Chinese leader Xi Jinping acts on his vow to “reunite” the self-governing island with the Communist mainland.

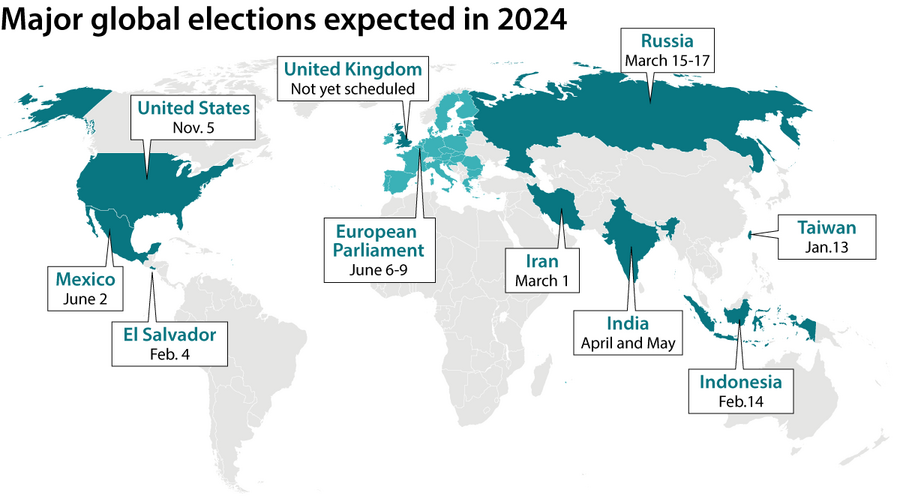

But there’s another reason to pay attention. In what has been dubbed “the year of the election,” not just Americans but 2 billion people worldwide are due to go to the polls in 2024. Taiwan’s vote is notable for being free and fair.

Why We Wrote This

In “the year of the election,” around 2 billion voters worldwide will go to the polls. But different countries use elections for very different purposes.

Many other elections will not be democratic. But two powerful messages are likely to emerge from this worldwide election year. The first is that even established democracies are under serious strain from eroding public trust in government institutions.

The second is that the core principle of democracy – that political legitimacy ultimately rests on the consent of the governed – is proving extraordinarily resilient. Even autocratic regimes feel the need for election victory, if not as a demonstration of support, then at least as a show of loyalty.

Their aim is twofold: to give their governments a sheen of democratic respectability in the eyes of the world, and to demonstrate to their own people the extent of their control. This time next year, we will know how successful they have been on those two fronts.

There’s a good reason the world is paying such rapt attention to this weekend’s election in Taiwan: The result could influence whether and when Chinese leader Xi Jinping acts on his vow to “reunite” the island democracy with the Communist mainland.

But in what has been dubbed “the year of the election” – not just Americans but 2 billion people worldwide are due to go to the polls in 2024 – something else distinguishes Taiwan’s vote from many of the roughly 70 others being held in coming months.

It will be free and fair, with a level field for the competing parties.

Why We Wrote This

In “the year of the election,” around 2 billion voters worldwide will go to the polls. But different countries use elections for very different purposes.

Elections in some other democracies – including two of the world’s largest, Indonesia and India – will fall short of that standard. In an autocracy like Russia, the result is a foregone conclusion. In Iran, the country’s religious rulers will decide who may run in legislative elections and who may not.

Still, two powerful messages are likely to emerge from this worldwide election year by the time the United States goes to the polls in November in the most closely watched race of all.

The first is that even established democracies are under serious strain from eroding public trust in government institutions and an increasingly angry, polarized political climate.

But the second is that the core principle of democracy – that political legitimacy ultimately rests on the consent of the governed – is proving extraordinarily resilient. Even autocratic regimes feel the need for election victory, if not as a demonstration of support, then at least as a show of loyalty.

Some elections this year will demonstrate the power of that core democratic principle in action.

South Korea’s in April, like Taiwan’s, could have international implications. The country’s delicate relationship with North Korea and recent rapprochement with Japan are in play. In Britain, with an election expected by the end of the year, the center-left Labour Party seems poised to end 14 years of Conservative rule.

Voters in the 27 member states of the European Union will elect new members of the bloc’s Parliament, amid signs of possible gains by far-right candidates calling for tougher policies on immigration.

Mexico will get its first female president this year: Both leading candidates are women.

In a number of other democracies, however, the potential fragility of their core institutions and political fabric will be on show.

That includes the U.S., the world’s wealthiest, most powerful, and most influential democracy.

As the primary season begins in Iowa next week, the political mood is fractious. The November election will be held under the shadow of efforts by the last president, Donald Trump, to prevent certification of his defeat in the 2020 election, which he and millions of supporters still insist was fraudulent.

Yet in a pair of autocracies voting in March, the second part of the election year message – the staying power of democracy as a governing principle – is also in evidence.

The most powerful sign is that President Vladimir Putin in Russia and the ruling ayatollahs in Iran feel the need to hold elections at all.

Their aim is twofold: to give their governments a sheen of democratic respectability in the eyes of the world, and to demonstrate to their own people the extent of their control.

Especially this year, both countries’ leaders are aware that even a carefully stage-managed election is not without political risk.

For Mr. Putin, this will be the first election since a constitutional change allowed him to run for a further two terms. It’s also the first since his disastrously miscalculated February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and last year’s march toward Moscow by mutinous Wagner Group mercenaries.

Mr. Putin will win, comfortably. But he’s taking no chances.

Even a little-known candidate calling for an end to the Ukraine war has been prevented from running. The best-known opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, has been jailed – first in central Russia and, since last month, in a labor camp above the Arctic Circle.

Iran’s supreme Islamic leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, will be equally confident of the election outcome: A council of guardians, and ultimately Mr. Khamenei himself, can bar candidates deemed unsuitable from running.

But the election, for Iran’s parliament, follows the most serious unrest since the Islamic revolution in the late 1970s. For months last year, demonstrators risked, and sometimes lost, their lives to protest the regime’s punishment of women for disobeying strict headscarf rules.

The goal in both Russia and Iran will be to ensure a high turnout, to avoid any impression that support for the authorities is on the wane. But leaders in both countries will know that democracies are inherently unpredictable, however carefully they are managed.

They need only look back to an election last year, in the former Soviet bloc state of Poland.

It had been ruled for nearly a decade by the right-wing Law and Justice Party, tightening its hold on power by reining in both the judiciary and the news media.

But a coalition of opposition parties, united in pledging to reverse these curbs on democracy, startled not only the incumbent government but also itself.

With record turnout, buoyed by support from women and younger voters, it won a majority.