(RNS) — President Donald Trump began his second administration much as he did his first: by flouting the tenets of American civil religion that inaugural addresses traditionally embody. This failure to exhibit moral gravitas, instill civic unity and extol American exceptionalism underscored President Joe Biden’s inability to restore “the soul of America” beyond his own administration. Trump’s proclamation of “Liberation Day” and pledge to usher in a “new golden age” announces what, one day, may be called the beginning of a Second American Republic.

While every inaugural address serves several functions — to lay out a new president’s agenda, to reflect on the nation’s past, to identify challenges and opportunities facing its citizens — its most essential purpose is to reinforce the American civil religion, which recognizes America’s distinctive character and the history of its democratic experiment.

Civil religion enables a pluralistic people to appreciate the American experience of self-government in light of higher truths, through reference to a shared heritage of beliefs, stories, ideas, symbols and events. Civil religion forms the basis of civic unity — the unum that our pluribus forms. Presidential inaugurations exhibit three facets of our civil religion — the priestly, the prophetic and the political — all of which Trump’s inaugural address ignored or transgressed.

The ceremonial — or what historian Martin Marty calls the “priestly” — dimension of civil religion entails the divine legitimation of the American experiment. Ceremonial features are observable in the prayers, oaths, supplications, blessings and idioms that suffuse an inauguration’s pageantry and symbols — all of which were on display for the 60th time on Monday (Jan. 20). Beneath Constantino Brumidi’s soaring fresco “The Apotheosis of Washington” adorning the Capitol rotunda, we observed the official procession, the stirring remarks celebrating the majesty and endurance of democracy, priestly invocations and benedictions discerning God’s providence, the swearing-in and oath of office, and invocations of “sacred” texts such as the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches.

Such ceremonial features of civil religion communicate dignity, reverence and a moral gravitas that ought to extend to the inaugural address as well. Yet, these vanished with Trump’s frivolous calls to designate his own inauguration date as “Liberation Day” and, after four centuries, to rename the Gulf of Mexico. Trump’s pledge to “drill, baby, drill” and his declaration of transgenderism as a violation of U.S. government policy have no place in a solemn inaugural. No one should underestimate how serious Trump is about such policies. But nor should we understand him to be morally serious, compared with how past presidents have used their inaugurals to uphold the dignity of the office.

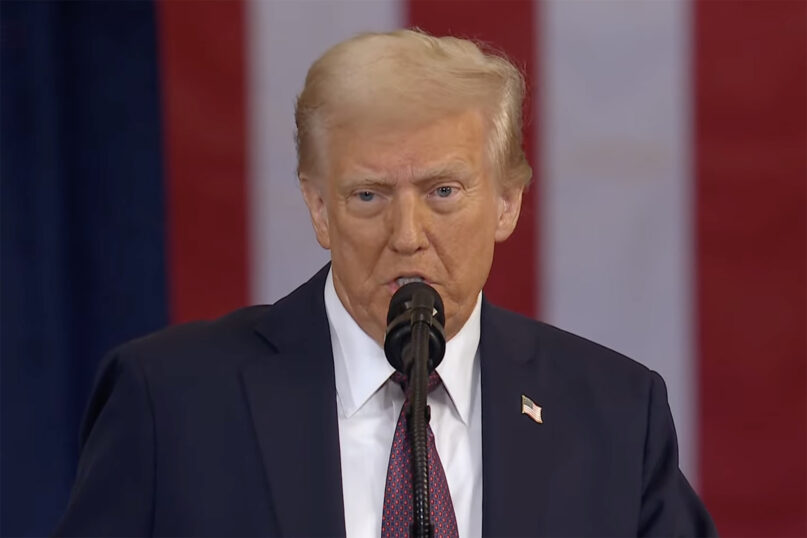

President Donald Trump delivers his inaugural address in the U.S. Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 20, 2025. (Video screen grab)

Perhaps more important than civil religion’s ceremonial or priestly strand is its “prophetic” cord that imparts Americans’ faith in democracy with moral meaning and political substance. Locating the American experiment with respect to divine reality does not place God on our side, but rather, as Lincoln wisely perceived, obliges that we endeavor to be on God’s side. (Kennedy’s inaugural similarly beseeched, “God’s work must truly be our own.”) Put differently, we know in a democracy that the will of the people can be wrong. Slavery, conquests, appalling cruelties and various forms of bigotry and persecution point to America’s failures to live up to its highest ideals.

The prophetic role of inaugural addresses reminds the people of the higher ethical criterion to which they and their government are accountable. Trump’s inaugural, however, suggests that acknowledging this higher criterion and our historical failures to honor it teaches “our children to be ashamed of themselves” and “to hate our country.”

Inaugurals also establish principles and promises to which the president personally will be held to account. So when Trump pledged, “We will be a nation … full of compassion,” he established a standard he immediately violated by scathingly condemning a bishop who implored him to “have mercy upon the people in our country who are scared now.” As well, having pledged to rebalance the scales of justice, Trump immediately issued more than 1,500 pardons and commutations for Jan. 6 offenders. Even William McKinley, whom Trump praised in his speech, used his inaugural to condemn mob violence: “Courts, not mobs, must execute the penalties of the law.”

Trump’s inaugural — a mashup of old campaign speeches, victory rallies and social media posts — made the nation’s standard for “greatness” an echo of his own narcissistic need for admiration. He prophesied that his victory might be “remembered as the greatest and most consequential election in the history of our country” and, evidencing the dangers when civil religion takes a messianic turn, he asserted: “My life was saved for a reason. I was saved by God to make America great again.”

Such braggadocio reduces his call to make America “more exceptional than ever” to just another vapid entry in his catalog of glory-seeking superlatives. Trump entirely forsook the “exemplar” strand of American exceptionalism evoked by other presidents — including Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama — that hails the United States as a beacon of hope, a shining city upon the hill, an indispensable nation. These are not merely self-congratulatory idioms to one-up other nations; rather, they evoke obligations and responsibilities to improve the world for all freedom-seeking people. This form of exceptionalism, however, is incompatible with Trump’s view whereby America “wins” by making other nations lose or fail.

Trump’s zero-sum view of American greatness not only breeds isolationism, transactionalism and grievance-based politics (which Trump repeated in his inaugural); it also ignores the historical gambit of past presidents — that the higher truths and universal pursuits that guide Americans are not scarce commodities to be hoarded but gifts to be compounded and shared throughout the world. As George H.W. Bush eloquently put it in his inaugural, “America is never wholly herself unless she is engaged in high moral principle.”

With Trump’s inauguration occurring on the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, he missed a golden opportunity to channel the prophetic strand of civil religion that King embodied more than any other American. Trump’s call to make King’s dream a reality was little more than lip service — invoked immediately after thanking Blacks and Hispanics for casting their votes for him. Nor did Trump’s calls to end affirmative action, restore “manifest destiny” and expand the nation’s territory reflect King’s views of how to make America worthy of its greatness.

Finally, civil religion also contains an important political strand. As the moral backbone of the body politic, civil religion imparts the republic with a spine that holds the rest of the body together. For this reason, themes of unity are prominent in inaugural messages. Outgoing presidents participate in the peaceful transfer of power. Incoming presidents reach out to those Americans who did not vote for them, pledging to be their president too.

Like Presidents Reagan, George W. Bush and Obama, President Trump thanked his predecessor — but only in his first inaugural, not his second. Biden’s inaugural was steeped in efforts to forge unity after Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 election. Urging every American to join him in the cause of “uniting our people, uniting our nation,” Biden expatiated on how “history, faith and reason show the way.” Recalling a famous passage from Augustine’s “City of God,” he urged Americans to find unity in the common objects of our love: “opportunity, security, liberty, dignity, respect, honor and, yes, the truth.” Such unity is essential to “restore the soul and secure the future of America,” he implored. Trump’s inaugural emphasized wealth, power and winning as the basis of “greatness.”

Indeed, the grandiose rhetoric of Trump’s inaugural disrupts the continuity that past inaugurals strenuously preserve. As he took office on “Liberation Day” to reclaim American sovereignty — from whom he doesn’t say — Trump promised a “new golden age” had begun. Our former republic — preserved by various facets of civil religion — seems poised to give way to a Second American Republic defined by Trump’s boundless ambition, avarice and conceit.

And so it falls now to those who cherish that old-time civil religion — and to new faces of our democratic faith (consider inaugural poet Amanda Gorman) — to preserve the “higher truths” that guide us and to invigorate the moral aspirations of our body politic. A nation that stands “under higher judgment” must seek correction, remain open to humility and recall the psalmist’s assurance echoed in Lincoln’s second inaugural that “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” There, Lincoln fittingly reminded a deeply divided nation that the judgment for failing to reckon with its sins could be devastating.

From Lincoln to King to the psalmists in our midst, I fear the prophets of our civil religion still have much to teach us — even when the president does not.

(John D. Carlson is an associate professor of religious studies at Arizona State University, where he also directs the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict. The views expressed in this opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)